in defence of 'sad girl books'

sad girl books about women in their twenties are a booktok staple - but is it overdone?

If you’ve spent any time on Booktok, you would have seen many videos about ‘sad girl books’. While this ‘genre’ is nothing new - think Sylvia Plath, Jean Rhys, Clarice Lispector - there’s no denying that these types of books have been dominating the publishing industry in the last few years.

The definition of the ‘sad girl novel’ seems to be constantly in flux, but I would sum it up as a book that features a female protagonist in her twenties or thirties who may or may not be mentally ill, who is living in a big city somewhere with an unfulfilling job while her romantic life is in shambles.

These books are also often referred to as ‘cool girl books’ or ‘hot girl books’, two terms which are used interchangeably but similarly describe novels that explore the experience of womanhood and bear the same overall hazy mood.

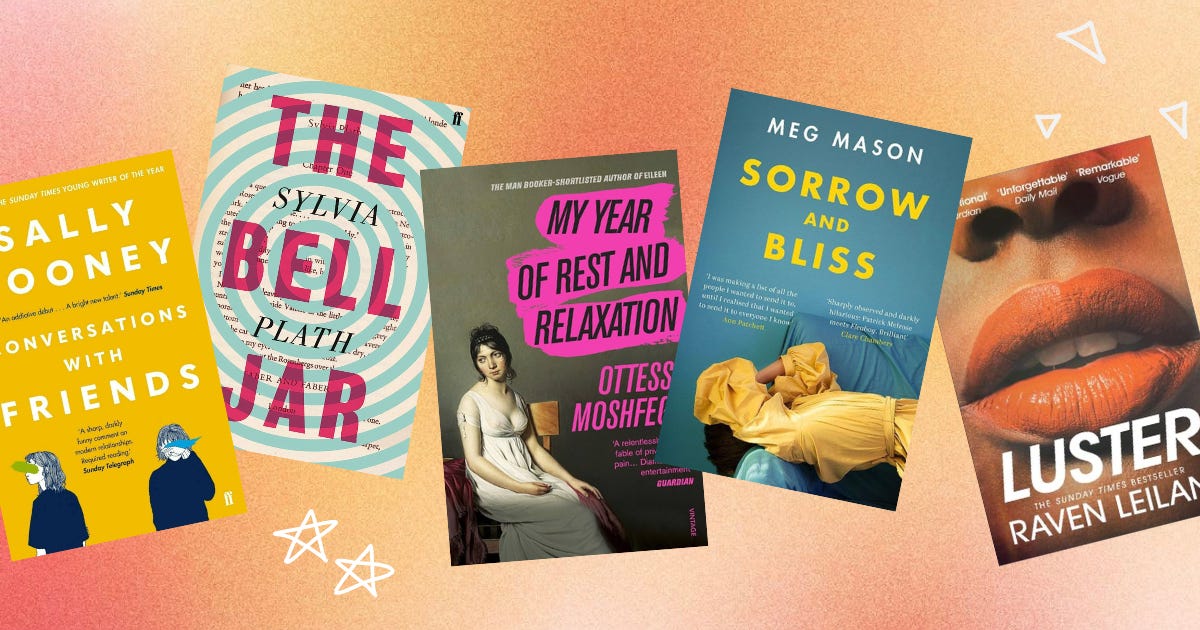

If you Google ‘sad girl novels’, some of the top books that appear are Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar (obviously), Sally Rooney’s Normal People, and My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh. The latter is perhaps the most interesting result, as despite the fact that the novel is a satire of the genre and Moshfegh has stated that her sad girl fans ‘concern’ her, it has still arguably become the, if not one of, poster girl for ‘sad girl novels’.

With its rise in prominence, both the term ‘sad girl novels’ and the books themselves have been criticised in strings of articles and in online discourse. Undoubtedly one of the most popular and valid criticisms is that ‘sad girl lit’ is a genre centring on the experiences of privileged, thin, white women who materially have everything they need yet remain crushed by self-loathing.

There have been attempts to slot a handful of books by authors of colour into the sad girl canon - Luster by Raven Leilani is a popular option, along with Candice Carty-Williams’ Queenie and Chantal V. Johnson’s Post-Traumatic. However, the fact that these novels do not enjoy the same levels of popularity and online fervour remains a problem and works to further exacerbate the overall whiteness of the genre.

An article in Slate argued that the kinds of narratives featured in ‘sad girl books’ don’t comment on the honest realities of being a woman, but instead celebrate their ‘female abjection’. In a society where depression is one of the leading mental illnesses, it’s been proclaimed that these romanticised depictions of sadness do not offer comfortingly relatability, but instead encourage stagnation and negate the desire to get help.

Similarly, the common theme of the protagonists in these books dating men who are, quite frankly, horrible to them, amplifies a narrative which journalist Moya Lothian-McLean described as ‘romantic victimisation’. On this account, ‘sad girl novels’ have been regularly questioned for just being ‘plain regressive’.

When it comes to the popularity of ‘sad girl books’ online, I am in no way an innocent bystander. In fact, ‘sad girl in your 20s’ books kind of became my content niche for a while. Going through my TikTok while writing this, I found around 10 different videos which featured these kind of book recommendations. For example, this video alone has almost half a million views, and this one has over 100,000.

Back in the heyday of Instagram bookclubs sometime in 2021, I even had a bookclub called ‘sad twenty something bookclub’ (RIP) which had over 1,000 members on discord. During this time I regularly received comments and messages from people telling me I had helped them discover this new ‘genre’ which they now loved. (Am I the drama? I don’t think I’m the drama…).

Of course, I’m in no way taking credit for this and am not claiming to be some kind of pioneer of the ‘sad girl’ genre or its popularity. As stated at the beginning of this post, these types of books have been around for decades. But I did make my TikTok account at a time when Booktok was in its very early stages. ‘Sad girl books’ were a large portion of the books I was reading at the time, and as one of the handful of Booktok creators who weren’t predominately posting about YA or fantasy books, these books consequently made up a lot of my content.

It’s not surprising that a generation who lost their late teens and early twenties to a pandemic would gravitate towards novels that explore how to navigate these turbulent years, especially when they’ve been deprived of the real-life experiences.

Yes, the term ‘sad girl novels’ is over-used and maybe a bit silly, but it’s just a digestible label put on a group of books which explore the trials and tribulations of modern womanhood. Grouping something into a category or a tag is just how social media works, it’s an algorithmic advantage, it’s nothing new. When you actually pick up some of these books, you realise there is a lot more complexity beneath the faceless depressed woman on the cover.

For example, for all the ‘sad girl/cool girl/hot girl’ aestheticization of Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, the novel is largely about a young woman self-medicating because she is unable to cope with the grief of losing both parents in quick succession. Referring to it as a ‘sad girl novel’ may be frivolous, but I don’t think labelling a book this way suddenly completely diminishes the complexities found inside of it. If you’re a critical reader capable of understanding nuance, it won’t for you either.

The women in these books aren’t just merely sad damsels in distress lounging over the furniture and pouting in the mirror. Some of them may be, I’ve read a fair amount of ‘sad girl novels’ that seem to just be hopping on the trend but don’t have much substance besides. However, most of these books follow women as they navigate their anxieties, their fears, their desires. A lot of them feature women who are simply angry, and for good reason. The popularity of this kind of fiction speaks to the fact that many young women see their own experiences and struggles reflected in these books.

Has the market of ‘sad girl novels’ become over-saturated, pumping out books with plots and characters that can feel a bit monotonous? Of course, this happens with every media form that becomes popular. But amongst it all, there are still good novels in there. I for one will be picking out the gems and continuing to read them.

endnotes

I’m going to start using this section to share some things I’ve been enjoying lately, so here’s what I’ve been loving recently:

The song ‘Bird’ by Billie Marten

Red velvet cake! I baked some cupcakes for my family during my time off from work, then I decided to make my own red velvet cake for my birthday, and then I used the leftover ingredients to make cupcakes to take into the office. I’ve been using this recipe from Jane’s Patisserie and the cakes are stunning (if I do say so myself).

The poem ‘St. Paul and All That’ by Frank O’Hara

Ana Wallace Johnson’s YouTube channel.

This white maxi skirt from Hollister. I basically wore it all summer and am excited to style it for some autumnal outfits.

I’m attempting to read the Booker Prize 2024 longlist/shortlist and have read 3 out of 13 so far…..But it’s a fun challenge and I’ve enjoyed all the books I’ve picked up to this point.

These are all fascinating thoughts! Like others, I bristle a bit at the label itself: books about men are just called “literary fiction” or “contemporary fiction.” Why do books about women need to be subdivided into women’s fiction, chick lit, beach reads, sad girl novels, etc?

The existence of “sad girl novels” implies that the default emotion of women should be something else (happiness, contentment), and that women aren’t allowed the full breadth of emotion the way men are.

I loved this! Especially your point about objectification