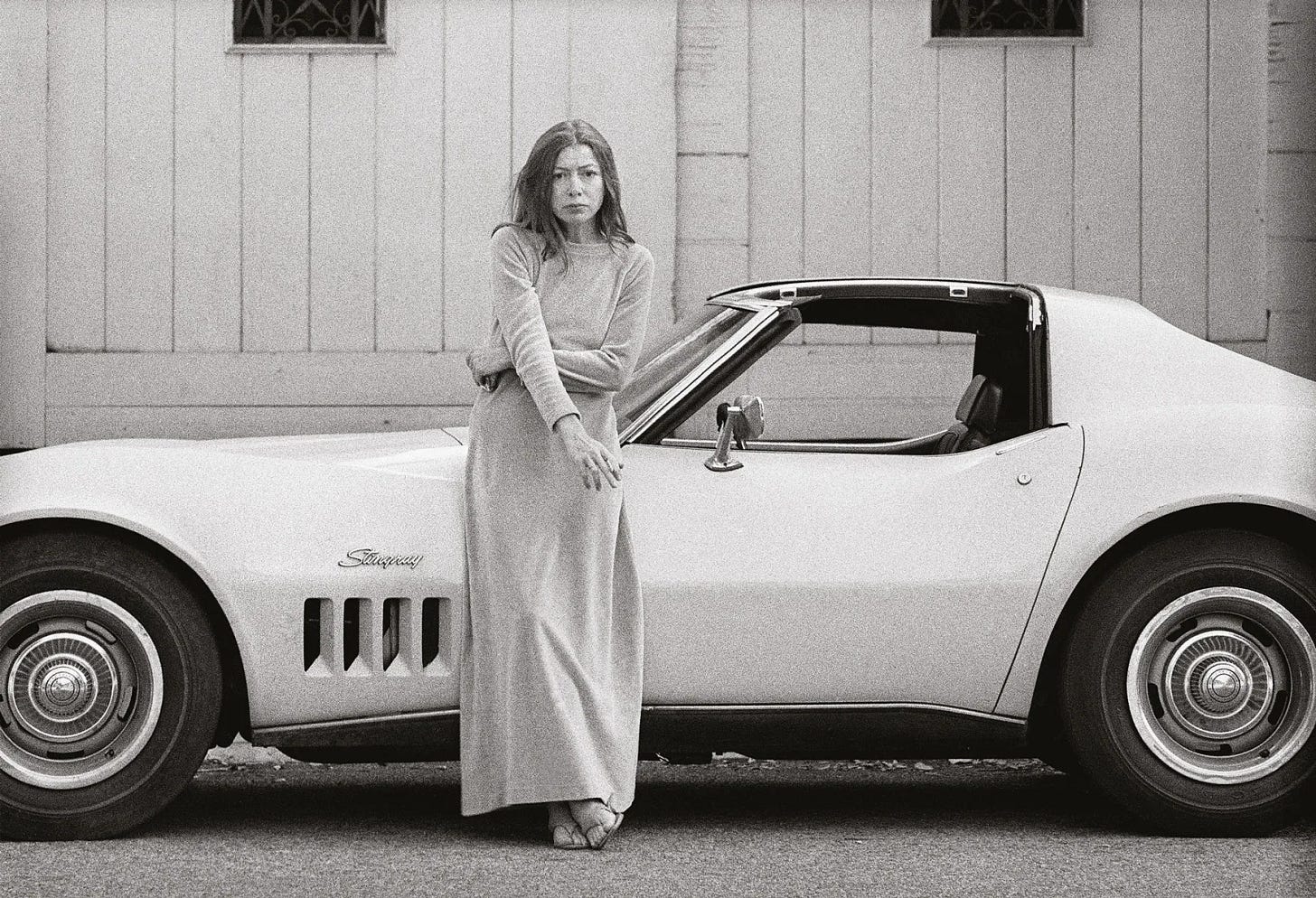

I can’t remember the first time I read Joan Didion’s writing, but I also can’t remember a time when I hadn’t read her writing. It feels like her influence has always been flickering in the back of my mind, her teachings teetering somewhere on the periphery of my psyche.

Her name has been mentioned in pretty much every lecture or seminar I’ve attended on the subject of writing. Though I didn’t study a journalism degree specifically, I studied at a journalism school where she was a frequent topic of discussion and an idol for many. Multiple copies of her books lined the library shelves in my university building, her iconic covers tucked under an arm or spilling out of someone’s bag. Echoes of her writing advice were uttered in seminars, the instruction that for every long sentence, you should add in a short one for the sake of rhythm - a style of writing Didion mastered.

To be like Joan Didion is no original endeavour, but it is an impossible one. She was a one of a kind talent. At the age of 22, she won an essay contest sponsored by Vogue magazine, bringing with it a job at the magazine and a move from her home of California to New York. So began her writing journey, a career which spanned decades and made her one of the most prolific writers of our generation. Along with being lauded as a defining voice of modern American literature, she is also cited as one of the pioneers of ‘New Journalism’, a journalistic style reminiscent of long-form non-fiction.

She is irrevocably an American writer, so as a British person, it may be surprising to some that I connect with her writing so deeply. Many of her books and essays centre on the American experience, focusing on the history and culture of California and United States politics. The fact that I oftentimes don’t know a whole lot about the specifically American topics/references she writes about just speaks to how engaging her writing is.

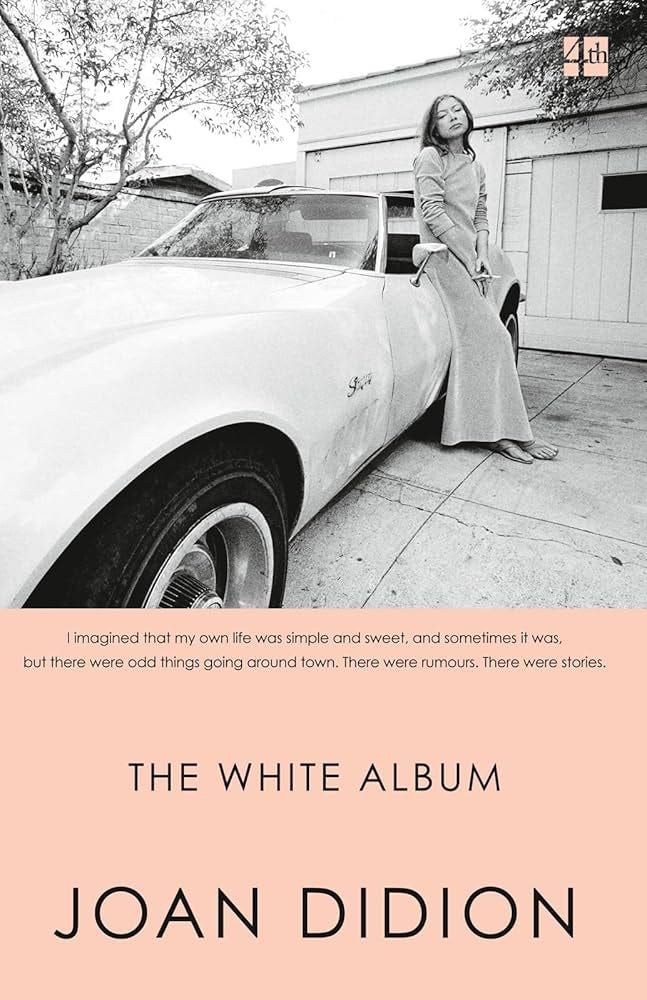

I had read excerpts of Joan Didion’s writing as I was growing up, an article here, an essay there. A copy of The White Album made it into my hands as a teenager, although I don’t remember much about that reading experience. It wasn’t until I picked up the book again in my early twenties that I realised just how good she was. Maybe I just needed to experience a bit more of life to fully connect with her writing, but I knew undoubtedly that Joan Didion was one of my favourite writers.

With this reading guide I am not claiming to be a Joan Didion expert. Neither is this a definitive list, as I haven’t read every single book Joan Didion has published, though I am working my way through her catalogue. But I believe I have read a fair amount to be familiar with her work and recommend where you should get started, depending on what you’re looking for.

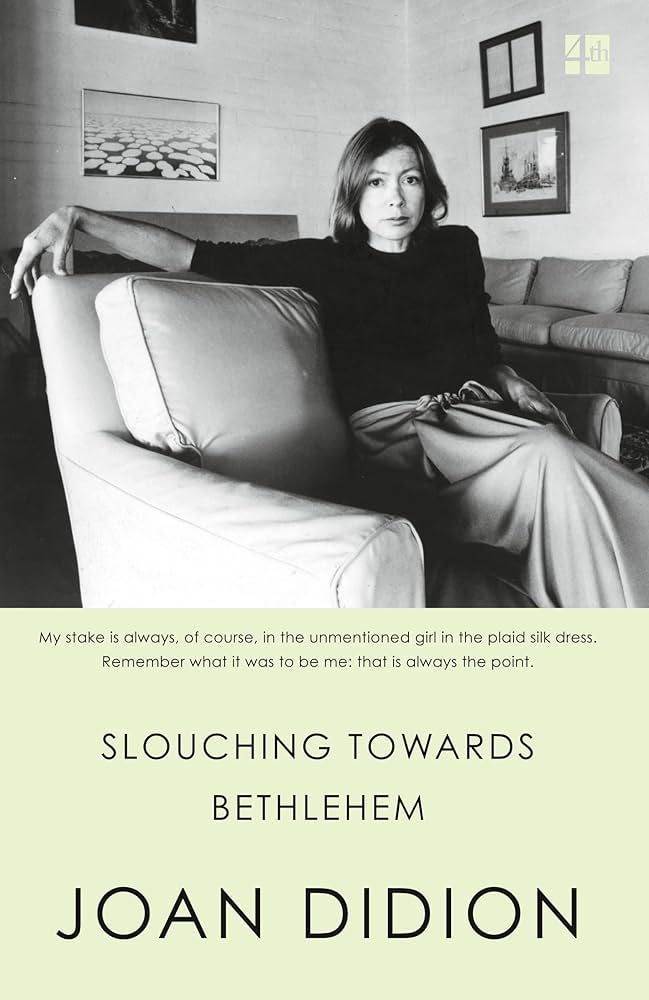

Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968)

Slouching Towards Bethlehem was Didion’s first non-fiction book, a collection made up of her previous columns and articles. If you haven’t read any Didion before, I often recommend this book as a good place to start.

Like with any piece of writing from Didion, she always approaches her subjects with such precision and purpose. Every language choice is intentional, every sentence is so eloquent, every detail meticulously written. She perfectly captures time and place, casting her critical eye on 1960s California and its cultural politics. A lot of the essays in this collection are unarguably bleak, one essay is about a murder case, while the titular essay focuses on the countercultural milieu of San Francisco, featuring a 5-year-old girl named Susan who takes acid.

But what makes Didion’s re-telling of events so engaging is how she manages to capture that bleakness with so much beauty, somehow making me nostalgic for a place and time I never even experienced.

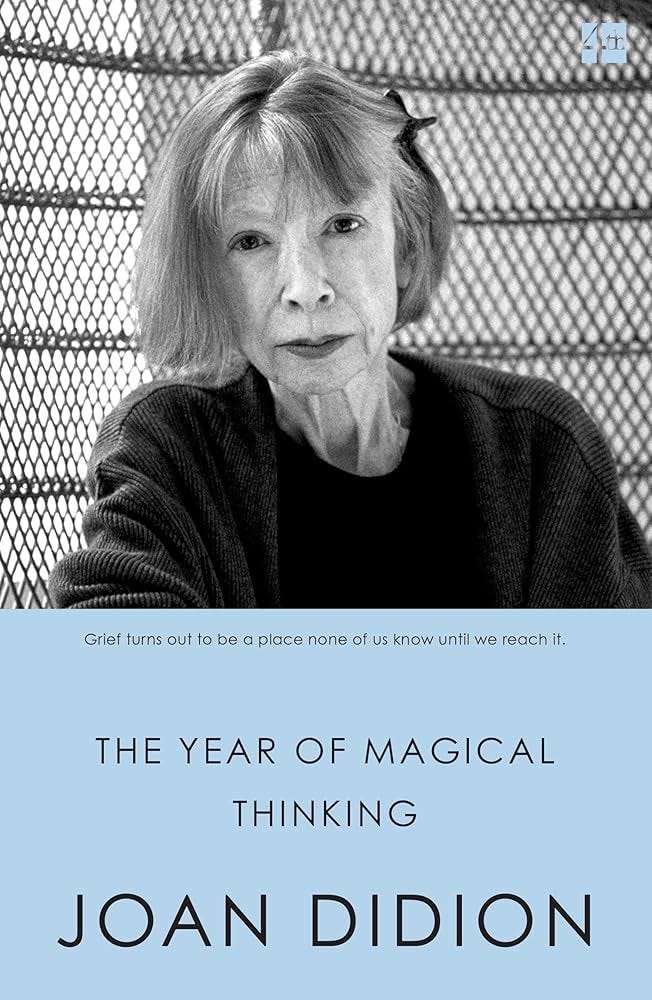

The Year of Magical Thinking (2005)

The only full book of Didion’s that I had read before this was The White Album, and my favourite essays within that were the more personal ones, the essays where Didion moves the curtain to give us a peek into her own life. In The Year of Magical Thinking, Didion completely rips down the curtain, sharing the intimate details of her grieving process after the sudden death of her husband and simultaneous hospitalisation of her daughter.

Didion’s writing is a master class in the art of brevity, her exploration of grief cutting to the bone with its honesty and frankness. As she has been taught to do since childhood, Didion takes refuge in literature, analysing grief and citing research on its effects. She desperately seeks the answers for the question of self-pity and to understand grief itself. In so doing, she allows the reader to understand it a little better too.

Although the book is specific to Didion’s own life and loss, it’s still possible to find relatability within its pages, which just speaks to the universality of the human experience. The course of life renders grief inevitable, but I find some comfort in knowing that I can always revisit this book over the coming years. If you’re a fan of more personal writings and memoirs, pick this one up first.

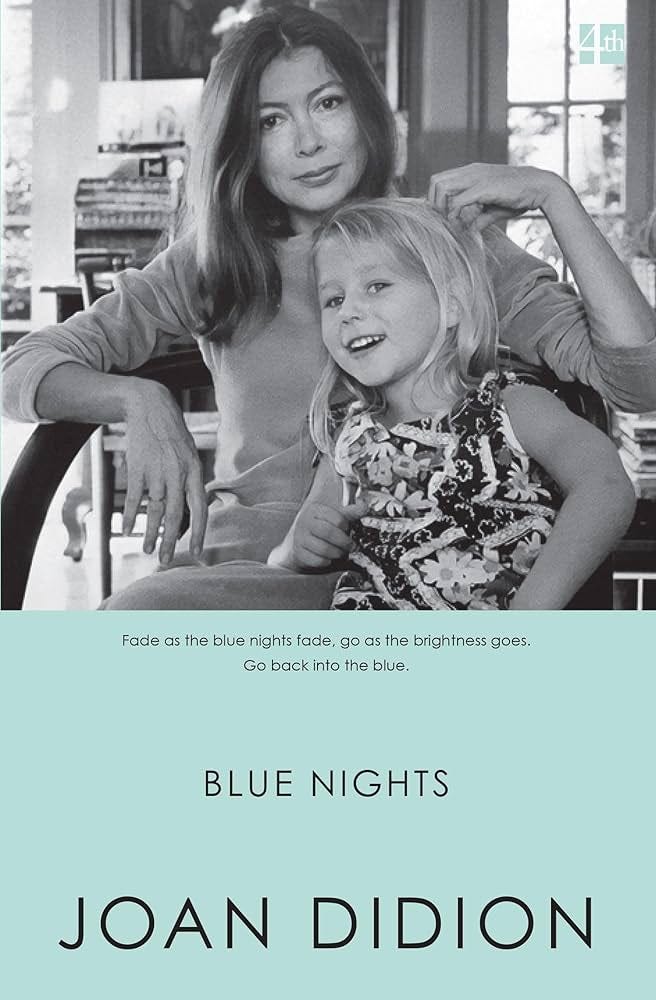

Blue Nights (2011)

Once you’ve read The Year of Magical Thinking, you need to pick up Blue Nights, a continuation of Didion’s reckoning with grief. It’s another instalment of her trying to make sense of life and death - two subjects which are, by their very nature, nonsensical. Like with every Didion, she doesn’t lecture, she doesn’t preach, she doesn’t claim to know any absolute truths. Here she simply reflects on her own personal experiences.

Hand in hand with grief, the predominant theme of this book centres on loss: the loss of her daughter, the loss of memories, the loss that accompanies ageing - or more simply, the loss of time. Didion struggles to accept the finality of ageing: the increasing frailty, the concern of others, but more specifically to her case, the loneliness of outliving those closest to you, of not knowing who to write down as your emergency contact at the hospital.

The issue of distance remains Didion’s most popular critique, and Blue Nights is possibly her most distant work yet. However, to me, the distance feels warranted, as it seems that Didion can only make sense of such debilitating loss by examining it from afar.

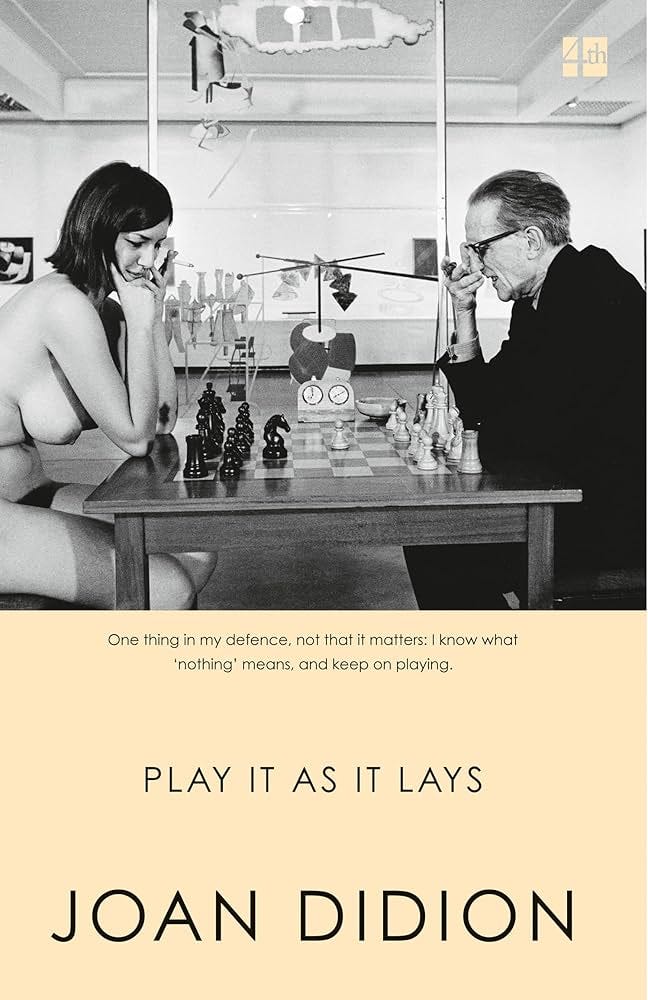

Play It As It Lays (1970)

Out of Didion’s 5 works of fiction, this is the first and only novel of Didion’s I have read, but it soon earned a spot on my list of favourite books. I had only ever read Didion’s non-fiction before this and despite owning this book for a while, I put it off out of fear that her foray into fiction may not compare. However, I now understand how wrong that was, because Didion’s pen shines just as brightly in fiction as it does in non-fiction.

Through hazy vignettes and tightly controlled prose, this novel tells the story of one woman’s downward spiral in late 60s LA. The book is, in Didion’s own words, exploring a character who is ‘coming to terms with the meaninglessness of experience’. Recalling the teachings of her father, the protagonist Maria lethargically drifts in and out of her world with the perspective that life is nothing but a game - a game she nihilistically accepts she will never win, but a game she continues to play nonetheless.

It is unequivocally an American novel, perfectly exemplifying the burnt-out cultural wasteland of 1960s California and its ennui. Although Didion worked on this book for years, Play It As It Lays feels bound by its cultural context at its time of publication in 1970, capturing the Californian malaise after the violent end to the summer of 1969 with the Tate–LaBianca murders.

It’s bleak, nihilistic, and quite frankly depressing, but that’s what makes it so great.

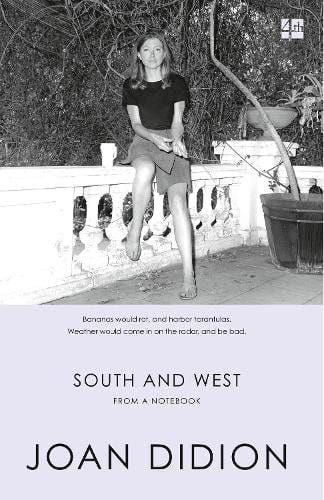

South and West: From a Notebook (2017)

South and West is made up of excerpts taken from the notebook Didion kept during her month-long road trip through the American South: a trip she took with the hope that it would become a piece. Though the article was never written, this book contains the notes and journal entries Didion wrote as she traversed her way through the Deep South, including states like Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama.

As usual, Didion casts her sharp eye on the places she visits and the people she meets, with her descriptions perfectly evoking the gothicism of the environment. We are privy to her experiences as she visits the French Quarter, bayous full of alligators, dusty gas stations and motels, which are all reported on with writing so atmospheric that you can almost feel the heavy humidity in the air.

The White Album (1979)

Ever heard the iconic phrase ‘we tell ourselves stories in order to live’? It’s the opening line of The White Album and a quote that’s adorned many tote bags since. Once again centring on California, these essays are Didion’s musings on the cultural and political upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s.

This book is great example of Didion’s style of examining, not explaining. If you don’t know the cultural references, she’s not going to hold your hand and talk you through it. You either know what she’s talking about or you don’t. I don’t know anything about American freeways or the Hoover dam, but I still enjoyed her writing about it.

I’d recommend to read this once you’ve familiarised yourself with some of Didion’s previous works. I personally don’t think it’s as strong as Slouching Towards Bethlehem, but of course there are still some great essays within.

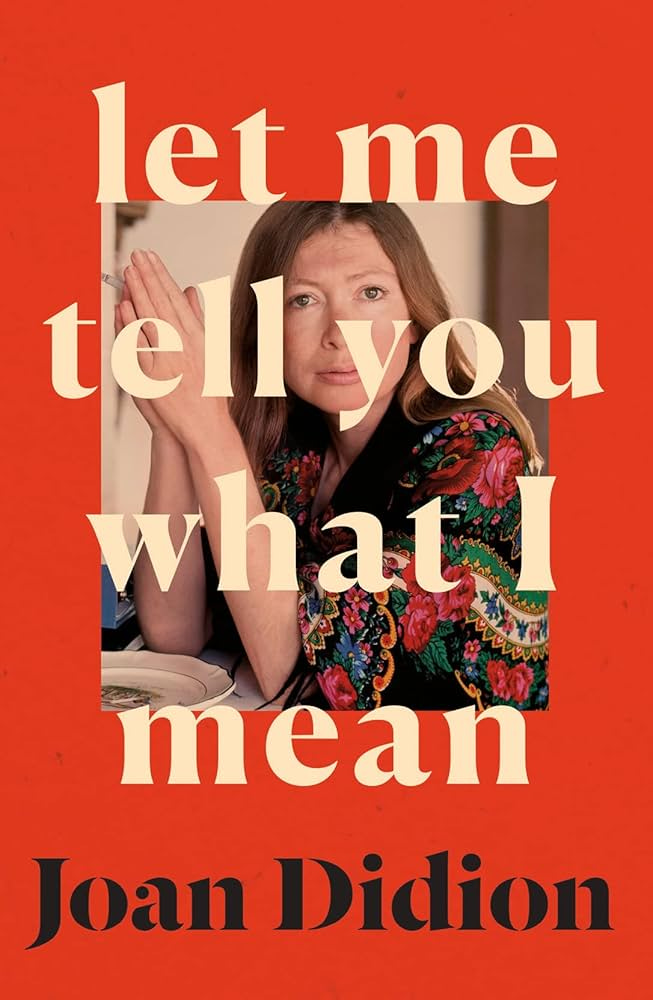

Let Me Tell You What I Mean (2021)

Let Me Tell You What I Mean is Didion’s most recently published essay collection, released just 11 months before her death in December 2021. Similarly to her previous collections, the pieces are a mixture of journalism, memoir, and criticism.

Didion pens her usual subjects in these essays: politics, the press, California, women, the act of writing, and self-doubt. There’s a profile on Martha Stewart, reflections on a Gamblers Anonymous meeting she attended, her experience of being rejected from Stanford University, and the well-lauded and often-quoted essay ‘Why I Write’ in which Didion explores her relationship with writing.

Once again, this is a collection you should read once you’re more familiar with her previous works and subjects. It’s not my favourite collection, but Didion simply doesn’t have a bad piece of work, and I’ll happily read what she has to say about anything.

Your writing feels like a hug after a long day, please keep on writing 💗

this is so so so incredibly well put together. thank you so much for taking the time and effort to put this together!